The Actual News:

With all the recent Gigaleaks and Megaleaks which have been revealing various mysterious bits of unknown and hidden Pokémon video game history to the masses… I must admit feeling like the Pokémon TCG has been left out in the cold a bit. Heck, not even a beta version of the Pokémon TCG Game Boy game surfaced! What rotten luck.

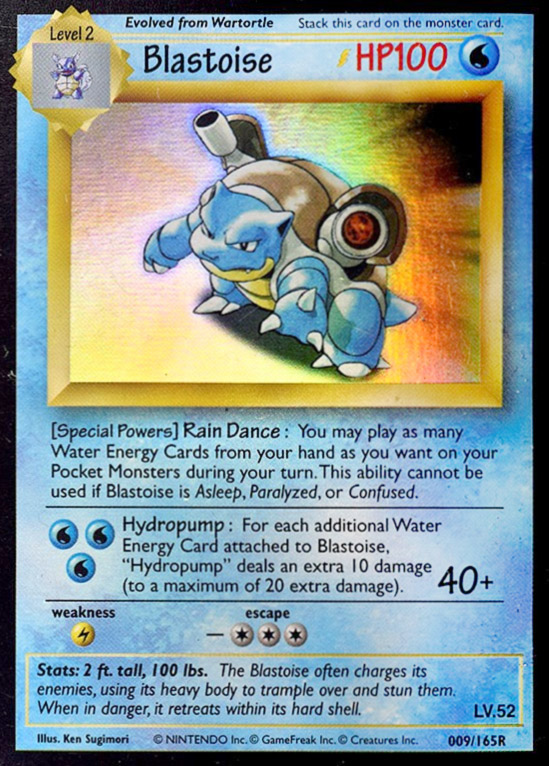

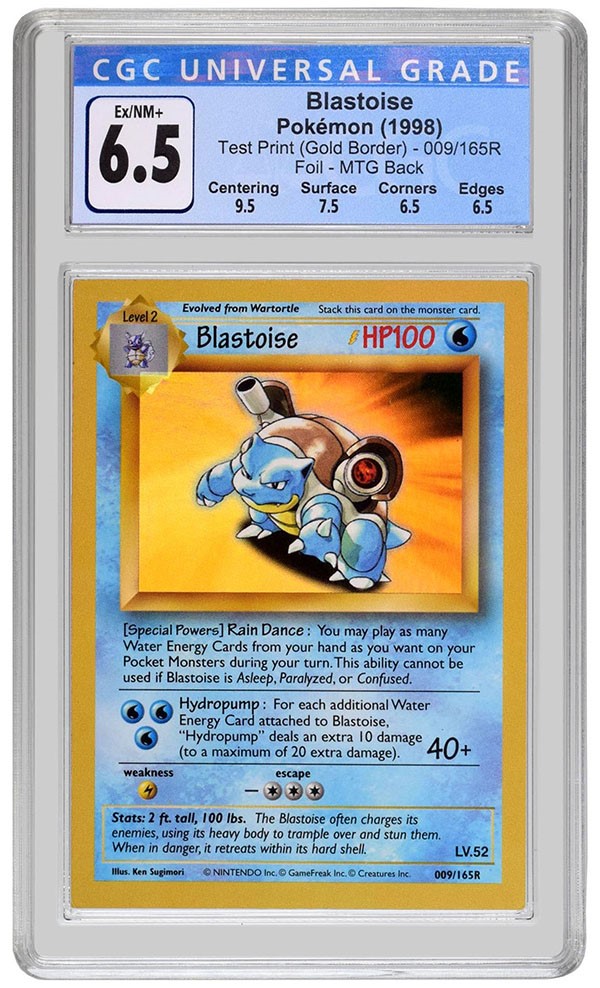

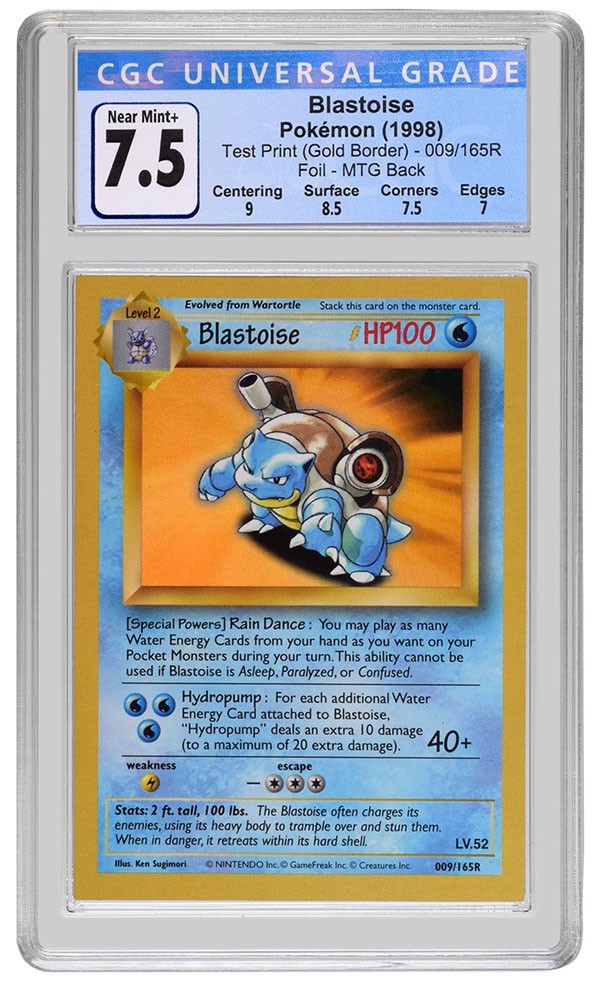

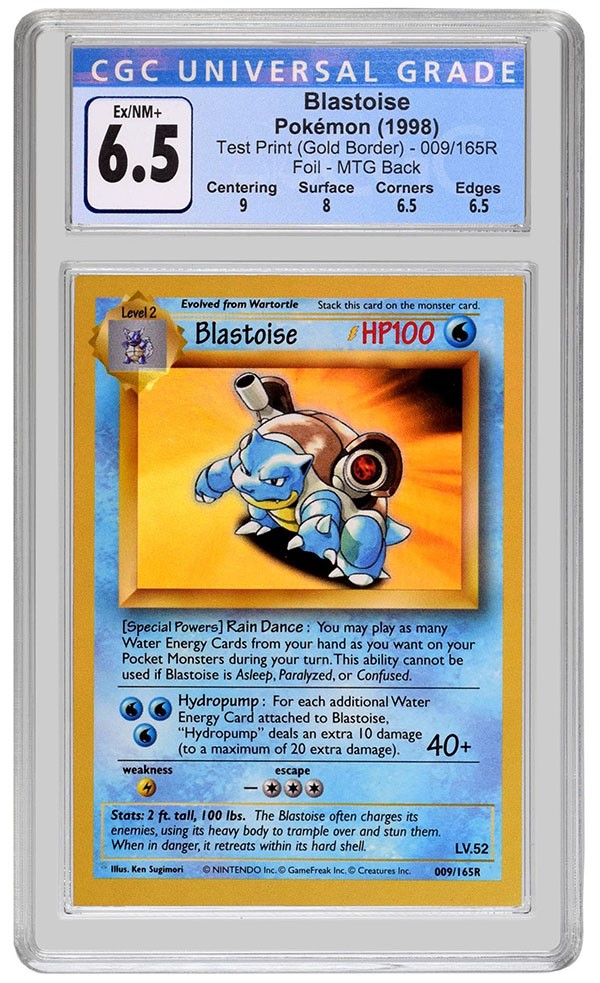

But recently I discovered something that simply knocked me off my socks. Initially I thought it was simply someone’s fake card that they managed to trick a professional card grader into sealing up for them… but the closer I looked into it, the more I realized that I stumbled upon something extremely important to the history of the Pokémon TCG. Here, take a look-see for yourself!

Wha…. what the heck is this??

Well, today I’ll give you the quick and simple story about how this card came about, but also break down everything there is to find out about this card… such as why making this Blastoise was the most PERFECT idea, to what exactly its mysterious “009/165” collector number might mean.

Just What Is This Card??

I first discovered this card—and, as I would later discover, it would be one of five known versions—on a Heritage Auction page for that card. The page itself describes its origins simply:

“Wizards of the Coast in mid-1998 commissioned Cartamundi to print two of these cards to be used as “Presentation” pieces to seek Nintendo’s approval to begin printing Pokémon cards in English. To add to the desirability, the card features one of the most popular Pokémon in the game, Blastoise!”

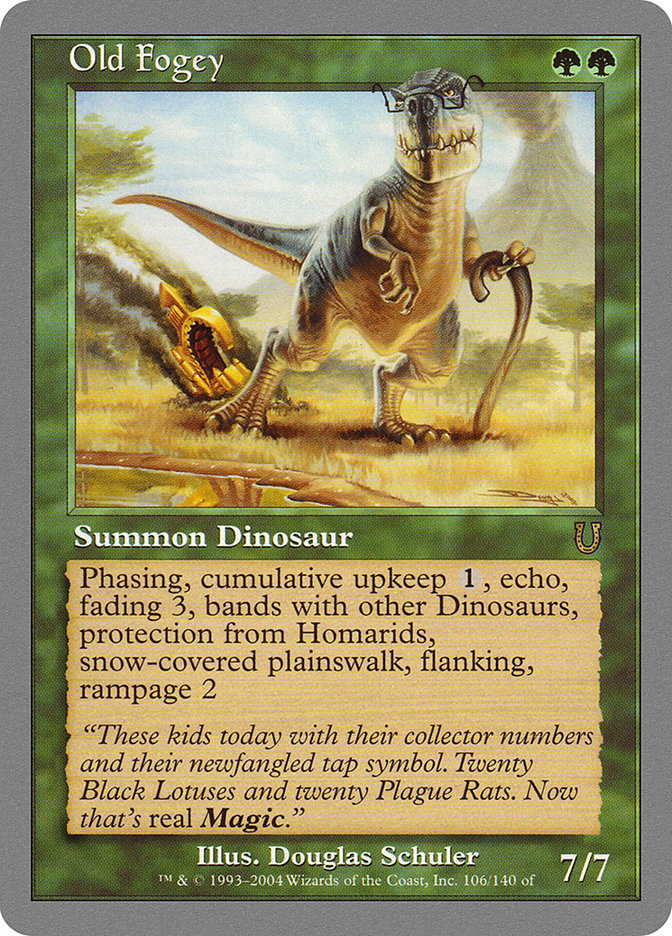

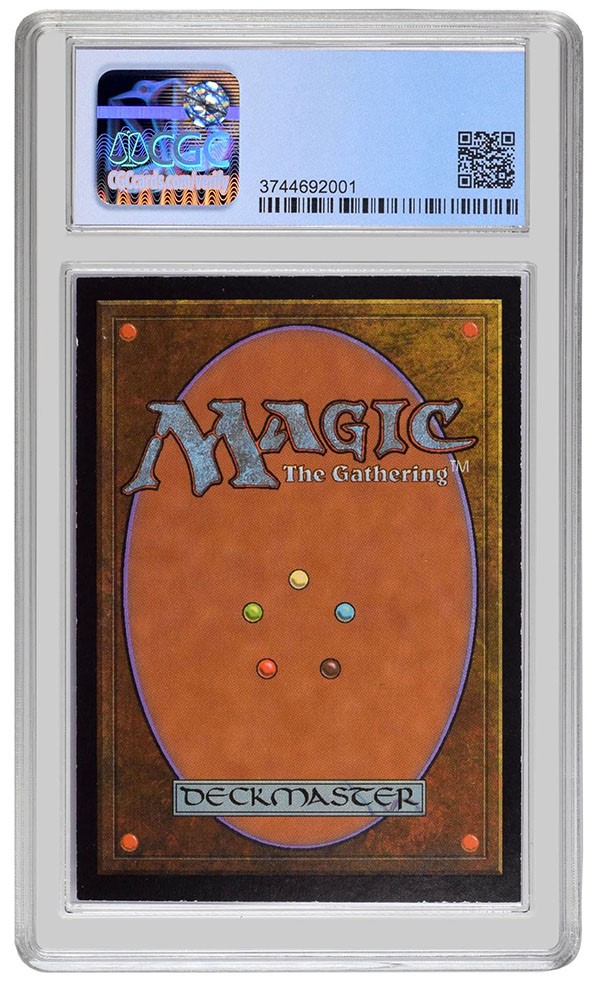

Just so you know, Cartamundi is a Belgian card printer, who have been printing Magic the Gathering since the very beginning and continues to print their cards to this very day. Since they were definitely printing for Wizards’ back in 1998, they surely would’ve been their go-to printer to help produce their first test English Pokémon TCG cards as well.

Anyways, the auction is long over, and this card ended up selling for $360,000! Holy crackers! Also, ignore the statement where it says that they had only two cards printed; as mentioned, this card is actually one of maybe five known versions. Four of them exist with a gold border and were graded by CGC Comics, and one with a black border which was owned by a Wizards’ employee who shared their copy to help with authentication. You should definitely read up on CGC Comics analysis of the cards on their website here, as they go through amazing details concerning where the cards came from and what they did to authenticate them. Now of the four versions of the Blastoise cards which were authenticated, three of them had a standard “Magic” foil and Magic: the Gathering card back, while the fourth had the Classic Holofoil and a plain white card back… this would be the one sold in the Heritage Auction.

As you can see, they made multiple different versions, but they’re all effectively the same card. Even the sole Black-bordered version is the same, although it does have a few minor differences which leads me to believe that it was produced AFTER the gold-bordered versions. Here’s a quick breakdown of these two versions:

The one on the left represents all four gold-bordered cards, which you can also see the holofoil cutting into the Evolution box, similar to how the Japanese cards did holos for a while. With the Black-bordered card on the right, you can see the holo going “behind” the Evolution box. Now as the CGC Comics article discusses, the Black-bordered card comes from a test print sheet full of other Magic cards which were also being tested, so they most likely mixed this sole Pokémon card into it to maximize printing capabilities; therefore, the Black-bordered Blastoise is more likely because it was mixed into the Magic sheet versus any plans to produce Black-bordered Pokémon TCG cards. In any case, other than the border and the holofoil style, these two cards—and their kin—are effectively the same.

That said, it would’ve been interesting to see where the use of black-bordered Pokémon TCG cards might have gone. Like, the use of a black border was something Wizards did with Magic cards back then… well, I guess they still do it today, technically. But more like, they utilized black borders to denote card releases; the alternative was the use of white borders (which were reserved for card reprints), gold borders (which were used for non-tournament legal reprints), and silver borders (which were used for other non-tournament legal cards). Furthermore, this was something they did a lot back when they distributed the Pokémon TCG, so it makes me wonder about whether or not Wizards’ might have done something similar with the Pokémon TCG if given the opportunity to.

Magic: The Gathering’s old borders: Black, White, Gold and Silver

Anyways……

So its history seems pretty straight-forward: Wizards was clearly trying to impress Nintendo while in the process of getting the license to produce and distribute the Pokémon TCG outside of Japan, so they made these cards. Clearly it worked, because… well, they ended up getting the license! But what makes this card so important to Pokémon TCG history? After all, this kind of prototyping is pretty common with all brands and products, so what separates this from any other prototype?

Well first off, just like with the Gigaleaks, this is simply a rare look into the initial design process of what is basically the second most popular trading card game in the world! Specifically, it’s the very first “behind the scenes” look in the Pokémon TCG’s English design process, both chronologically and what has actually been revealed to the public. It’s especially important because these Blastoise cards look significantly different from what would ultimately be in English’s “1st Edition Base Set” release.

On top of that, these cards are also basically the ONLY version of this particular card in English. That is to say, the card that Wizards based their “commissioned presentation” on ended up being the CD Promo Blastoise:

…but despite these cards being made, a subsequent English version of it would never end up being produced. So aside from these test prints, there are NO English “CD Promo Blastoise”.

When you put this all together… aside from them being a one-of-a-kind English version of a promo card which otherwise never saw a Western release, they are also a one-of-a-kind early printing of English Pokémon TCG cards. So a card that is doubly one-of-a-kind? I’d say that’s top tier importance! That said, the only thing that brings it down a notch in terms of ULTIMATE importance is the fact that Wizards was basically a licensee contracted to produce and distribute the English version of the game. They didn’t own the game itself. So in a certain way, it’s not AS “official” as if it was a Japanese card, but it’s certainly more official than if, say, I made a one-of-a-kind Pokémon TCG card myself. Still, this isn’t to completely discredit its importance and value in the grand scheme of things… if there ever was a pantheon of the most historically important cards in Pokémon TCG history, this would certainly belong in it before even “1st Edition Charizard” would!

Of course, this is simply the history portion of this discussion and if all you wanted to know was where this card came from… well, there we are. But there’s still quite a lot left to go over when it comes to actually processing the true historical value of this Blastoise… which includes working out how different this Blastoise is relative to the designs that ended up appearing in the final English release of 1st Edition Base Set on January 9th, 1999, and therefore getting an idea of how Wizards came to that design. Well, beyond simply copying Japan’s homework. In fact, Wizard’s choice of a card like Blastoise was perhaps the best choice they could’ve made in order to impress Nintendo with, as it really nearly is an entire design document for pretty much every other possible card design… and all wrapped up in a single card.

Blastoise: an Entire Pokémon TCG Style Guide in a Single Card

First off though, to get an idea of how different Prototype Blastoise is to the final product, here it is next to an Unlimited-style and 1st Edition Base Set Blastoise. Here you can get an idea of what kind of changes occurred between their first initial design test and what ended up being designed for the 1st Edition runs, then finally the Unlimited-style run where the cards looked even more like their Japanese counterparts (tho only just).

As mention above, Blastoise was perhaps the most perfect card Wizards’ could’ve chosen to recreate, because it so perfectly encapsulates so much about the card game’s design style, rules, etc, all in a single card. If Nintendo representatives had any questions about “what English word will you be using to denote THIS game play element” or “what would this other card look like with this number of Energy”, all they had to do was simply look at the Blastoise card, and I’d say 95% of their questions could be answers right away. The alternative would’ve been to simply design and print multiple cards to cover all those different potential questions and possibilities… but Wizards producing the Pokémon TCG was not some fore-gone conclusion just yet, I doubt they would’ve had the time and ability to draw up a multiple cards. Besides, clearly printing needless cards was costly and time consuming—otherwise Wizards wouldn’t have needed to attach those Blastoise test prints onto sheets with Magic cards on it!—so why not be more efficient and just design one in English card… but choose a card that covers as much of your bases as possible. Makes sense, right?

So to get an idea of how perfect this card is when trying to showcase the core style guide that could be applied to every other card—at least in Base Set, Jungle and Fossil—here’s a breakdown:

- Choosing a

StageLevel 2 Evolution card also implies what a Level 1 Evolution card would look like (Level 2 has two gold lines, so Level 1 would have only one) - Blastoise has both a Power (“Special Power” instead of “Pokémon Power”) and an Attack

- Though the word “attack” does not appear on the card itself.

- Both Rain Dance and Hydropump establishes how Energy card types would be referenced: instead of an Energy symbol, the Energy type is actually spelled out

- Rain Dance also shows that Special Conditions—Asleep, Paralyze and Confusion—would be written in italics, thus emphasizing the fact that those are Special Conditions instead of something else

- It also showed some of the primary game ruling, namely that you can otherwise only play a limited number Energy Card from your hand each turn.

- Technically it doesn’t say how many you’re limited to, but kinda implies a limit of one Energy per turn, by virtue of “as many … as you want”.

- Hydropump attack uses three Energy, showing what both a 1, 2, 3 AND 4-energy cost attack would look like

- That is to say, a 1-energy cost attack would look like that single middle Water energy on the bottom, while a 2-energy cost attack would look like the two Water energy on the top. And since we can see that a three-energy cost attack places energy in two rows, a FOUR-energy cost would simply be two rows of the 2-energy cost format

- Hydropump also was an attack that did extra damage, thus showing what other attacks using multipliers would look like.

- Furthermore, it was self-referential, thus establishing what other similar attacks would read like.

- It’s worth noting that Magic’s style guide back then used self-referencing a lot, while today… well, it still kinda does.

- Since Blastoise’s HP is three-digits (100), that’s the fullest extent of the space needed for any HP between 30 and 120

- That particular Blastoise is from a Japanese promotion involving trading cards (both the noun AND the verb), and then was released in a CD of various Pokémon songs… but the point is, it had a Set Symbol—a yellow lightning bolt—and that icon is placed right next to the HP. Therefore other sets—Jungle, Fossil, etc—would have their set symbols placed there.

- Of course, where the “1st Edition” symbol would go is unknown, but I highly suspect Wizards had no plans for that concept until much later.

- With a three-energy

retreatcost escape, it could be easily imagined of what cards with one- and two-energy costs would also look like… possibly even no-energy costs (just simply nothing after that em-dash). - Other style guide standards are also showcased, such as:

- what the action is to play something from your hand (“play”)

- what these creatures are called (“Pocket Monster(s)”, “monster card”)

- what kind of costs are involved in using them (“Energy”, “Energy Card”)

- where unplayed cards are held (“[your] hand”)

- when you can play your cards (“[your] turn”)

- the verb and adjective of placing additional cards onto your Pocket Monsters (“stack”, “attach”)

- how Pocket Monsters can defeat another (“[deal(s)] … damage”)

- if “Special Power” can be known as something else (“ability”)

The only thing missing from this card which it doesn’t address is:

- What a Basic

PokémonPocket Monster card would look like - What “Hydropump” actually is (since it was self-referential, it doesn’t actually call itself an “attack”)

- Where the Resistance would go

That’s pretty much everything missing… so I must say, choosing Blastoise was a pretty good choice for this purpose, as it clearly covered a LOT of different elements of game play in a single card.

- inb4 “Charizard has a Resistance!” Yeah but it doesn’t have an attack that does extra damage, and it arguably also isn’t self-referential. Plus its attack uses 4 Fire Energy, meaning you wouldn’t have an idea of what a 1-energy attack would look like

That said, I’m sure the folks at Wizards didn’t think THIS deeply when deciding which card they wanted to print to impress Nintendo with, but hey… maybe they did? I mean, maybe they didn’t bullet-point everything like I did, but once they had at least got Venusaur, Charizard and Blastoise translated, I’m sure they all looked at each other and nodded: “Blastoise. It’s just too obvious.” And yeah, now we know why!

A Breakdown of the Proto-ness

But now that we have a good idea of WHY they chose Blastoise to build their prototype card off of… what exactly is going on with this card? Why does it look so different?

Once again, here’s my breakdown. First tho, clearly they went with a bit more of a literal translation of the Japanese card elements, or at least use of its standards… so we see stuff like:

- “Level #” instead of “Stage #”

- “escape” instead of “retreat (cost)”

- “Evolved from” (past tense) instead of “Evolves from” (present/future tense)

- “Stack this card on the monster card.” instead of “Put XXXXX on the Stage 1/2 card”

- “Pocket Monster(s)” instead of “Pokémon”

- “Special Power” instead of “Pokémon Power”

- the literal use of “Water Energy Cards” versus ZW; this is because the original Japanese cards used Kanji forms of the Energy type instead of the actual Energy symbol

- The “Level” evolution box creeping out into the card border—like the original Japanese card design—instead of staying inside the card frame

- Incidentally, that evolution box design is the same one used in 1st Edition Shadowless Base Set cards, but was changed in subsequent Shadowed designs

- The use of two bars to denote “Level 2″—also like the original Japanese—but the English cards (even in 1st Edition Shadowless) used one bar, regardless of Stage number

- “HP100” instead of “100 HP”

- This makes me believe that the other “HP #0” errors in 1st Edition Base Set Metapod, Caterpie and Vulpix might have been because those were the first cards to be designed and the decision to swap “HP #0” to “#0 HP” came a bit later in the design process…

Other significant design changes include:

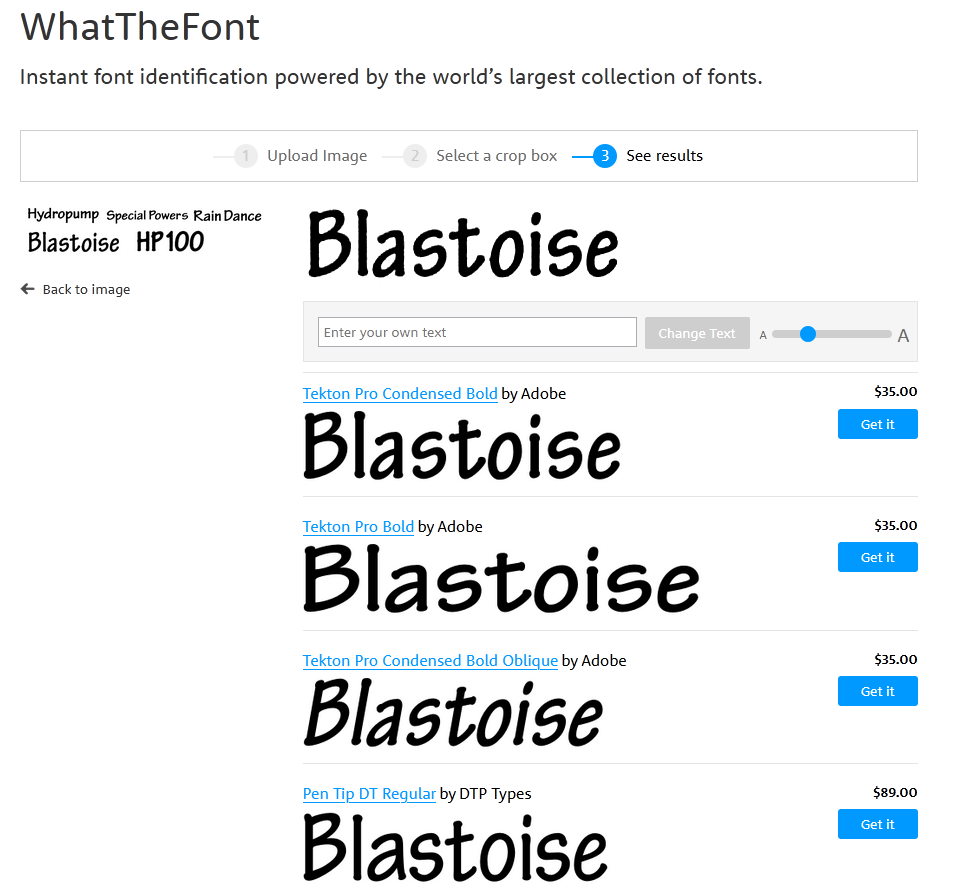

Let’s get the obvious one out of the way first: is that Comic Sans?!

Let’s get the obvious one out of the way first: is that Comic Sans?!

- Actually, no. I did a bit of research at WhatTheFont (see right) and instead it’s a typeface called Tekton Pro; it’s used for the Pokémon’s name, HP, Special Power name, Attack name and Damage amount.

- The rest of the card is good ol’ Gill Sans.

- There is ONE other typeface used: the “Level” in the lower-left corner of the Flavor Text box. It appears to simply be some variant of Helvetica.

- Card art is smaller, as is the Art Box area itself

- I mean, yeah, the Art Box border is thicker, but that overall area itself is a bit smaller… then the actual card artwork is smaller on top of that.

- As mentioned above, the Set Symbol was placed next to the HP instead of next to the Stat Box… which is mysteriously absent.

- More curious is that, whoever designed this Blastoise clearly saw that the corner between the Stat Box and the Art Border was a nice place for the Set Symbol… yet they made the deliberate choice to remove the Stat Bar and move the Set Symbol up by the HP.

- Speaking of the Stats, they got moved down to the Flavor Text box.

- The fact that its stats are located down there instead of a separate Stat Box is perhaps the most significant change between this prototype and a final card. Even the cart art with its thicker border… at least it has a border!

- Also whoever designed this had no concept of the metric system. It’s like they took Blastoise’s metric stats—1.6m, 85.5 Kg—dropped the quantifiers—1.6, 85.5—then rounded them up to some arbitrary value—2, 100—and called it good. “Hmmm… 1.6m, 85.5 Kg… that’s like, 2 ft and 100 pounds, right?”

- The Flavor Text box itself is… well it’s something.

- The flavor text has both the height of the Japanese version and the width of the English version. The flavor text itself is three full lines, and the Level value is shoved right in the corner. It ALSO doesn’t have Blastoise’s Pokédex number; though I think that might have been covered by its Collector Number (see below). Either way, I’m glad they made the Flavor Text box a much more efficient size in the end.

- Its flavor text itself is just a translation of its original Japanese card’s Pokédex entry: “It crushes its foe under its heavy body to cause fainting. In a pinch, it will withdraw inside its shell.” (体が重たく、のしかかって相手を気絶させる。ピンチのときは、カラにかくれる。) This entry in turn was based on its original Japanese Red/Green entry. This flavor text also exemplifies how Wizards used to translate the Pokédex entries into English before realizing that… well, Nintendo already did it for them. Directly translating them caused for some interesting Flavor Text errors in the early Pokémon TCG releases.

- Both the names of its Power and Attack are followed by a colon to separate it from its game text. Meanwhile in the final design, their names are separated from its game text by virtue of the names being larger and bolder.

- Its copyright info is different, but it’s still one more than the Japanese version ever had.

- Its collector number both has leading zeros (009 instead of simply 9), has the rarity tacked onto the end (instead of a symbol) and is… out of 165?

- I have an idea about that below… and it also may explain why Blastoise’s Pokédex number is not included in its Flavor Text.

All this said, this prototype design still does at least cover core Pokémon TCG card design in the broad strokes… name, type, evolution info, HP, powers, attacks, weakness and retreat info, as well as its flavor text, illustrator and collector number are are all where they’re supposed to be, the attack itself is ordered properly—Energy, Game Text, Damage—so honestly, it’s a lot closer to the final design than not, and this is especially considering of how strangely different it is in general.

My Fan Fakes and Fan Theories

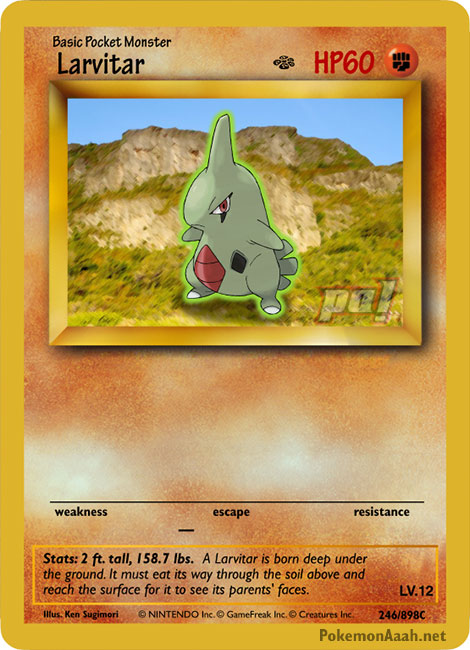

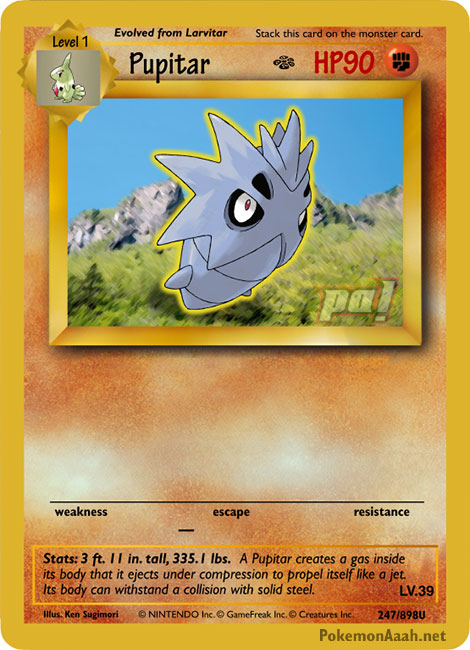

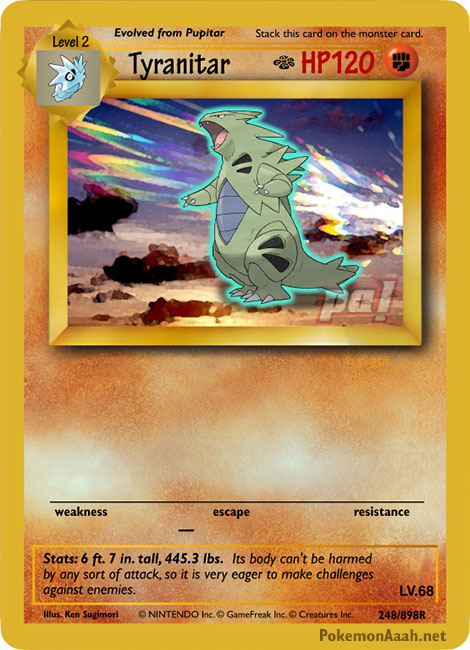

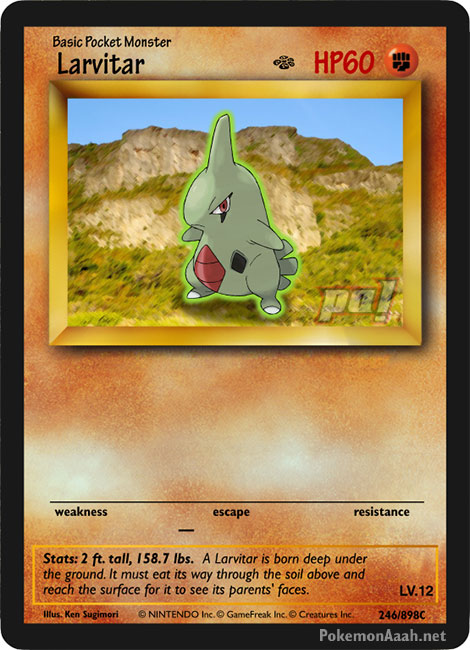

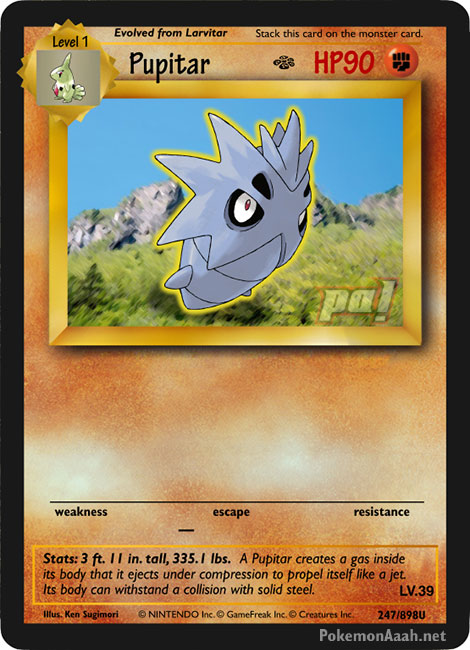

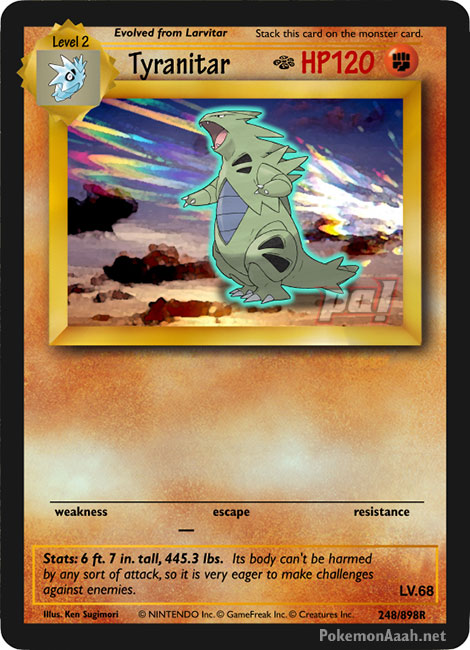

But perhaps best part about having this card lay out nearly all of the core design and style guidelines is… I can make fakes and blanks out of this! Yup, using my Neo Redux blanks as a base, I can very easily make a complete set of blanks in this format, complete with “Level” Evolution boxes poking into the border, larger Flavor Text box and set symbol located by the HP! Oh, and in both gold AND black borders. Take a look!

Of course I had to make a few guesses about some of the card elements, like what Basic Pokémon Pocket Monsters would look like (I mean, I used “Basic Pocket Monster”, but maybe I should stick with the standard “Basic Pokémon” for ruling compatibility?), where the resistance would go (I placed it to the right of “escape”, thus keeping “escape” in the middle, but maybe I should move “escape” over to the right where it normally is?)… but I think it’ll be a fun little project to do. … At least, once I’m finished with all the other blanks I need to make!

Anyways, there’s just one last mystery left about this card: why is it #9 out of 165? Normal Base Set Blastoise was #2/102, while the original Japanese CD Promo of Blastoise was #009, and only because that was its Pokédex number. OK so maybe that explains why its #009—as well as why its Pokédex number wasn’t in the Flavor Text box like it normally is—but what about the 165? Let’s think of a few ideas first:

- So maybe it’s Base Set plus Jungle, right? Well, that would be 102 + 48 (ignoring how the English set made holo and nonholo versions of the rares)… which is 150 cards.

- Base Set + Jungle + Fossil then? That’s 150 plus another 48 cards… lol nope

- Aha! Well, a little birdy once told me that Wizards actually gained the rights to the “Vending Machine” set from day one, despite never actually releasing it. So maybe they were gonna mix it with Base Set then? Well, Vending had 108 cards, and 102 + 108 is…. oof, not 165.

- I mean, I GUESS they could’ve just taken the best 63 cards from Vending and added it to Base Set, bringing it up to 165, but I highly doubt that.

- Perhaps it’s simply 151 Pokémon, plus X number of trainers from Base Set, Jungle and Fossil, thus a total of 165 cards, right? Weeeellll… there’s 26 Trainer cards alone in Base Set. And then ignoring Energy cards (which were also counted as part of the 102 card size of Base Set), that’s 177 cards.

So honestly, I can’t think of any other combination of cards that bring it up to 165! Well…. except for one last idea: “POKÉGODS”.

Reign of the PokéGods

Well, not literal Pokégods, but the name some fans gave to all of the post-Mew Pokémon that have been slowly dropped into the anime here and there—like Togepi and Snubbull—but were not part of the main list of official 151 Pokémon, and especially before “Johto” entered into everyone’s vocabulary. After all, this was 1998, and Gold/Silver had yet to be officially released… however news about its future was already beginning to be spread across both schoolyards and video gaming news sites alike. Knowledge of officially new Pokémon was out there, so maybe Wizards wanted to include their numbers to the 151 to show that they’re paying attention?

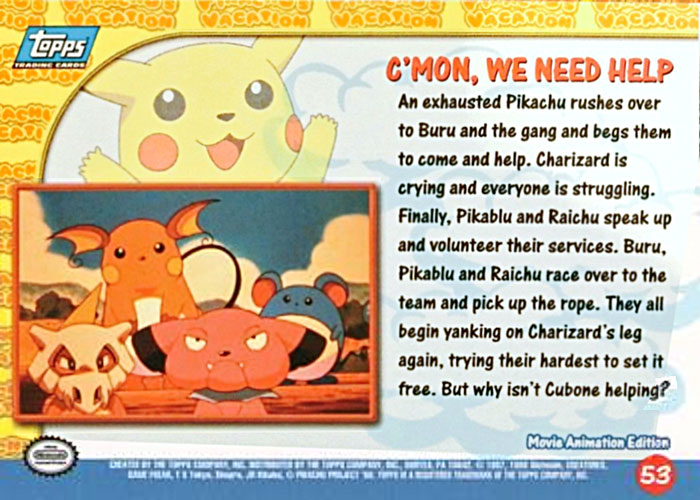

Ah yes, everyone remembers Buru and Pikablu!

Personally this makes the most amount of sense to me… so in that case, that would mean that Blastoise isn’t card #9 of a 165 cards set, but Pokémon #9 out of 165 total Pokémon. But… were there 14 GS Pokémon known back then to bring the total up from 151 to 165? Well, let’s put our thinking caps on… First off, by the 1998 Japanese release of Pikachu’s Vacation and Pokémon The First Movie, there was definitely:

- Ho-Oh (as seen in the very first episode)

- Togepi

- Marill

- Snubbull

- Donphan

…well, that’s five already, so maybe we’ll include the three starters:

- Chikorita

- Cyndaquil

- Totodile

…and that’s eight so far. Hmm… maybe if we include Pokémon introduced by the second movie release Pokémon The Movie 2000 and Pikachu’s Rescue Adventure:

- Elekid

- Bellossom

- Ledyba

- Hoothoot

- Lugia

- Slowking

That’s 14 Pokémon right there! This could very easily account for the 165 value on the Blastoise card. The ONLY slight issue might be that many of these didn’t appear in Japan until 1999, but then again maybe Wizards was privy to this information during initial meetings with Nintendo back in 1998, as I’m sure Nintendo had all this information sorted out by then. For example, perhaps Wizards wanted to get an idea of Nintendo’s long-term plans for the franchise—afterall, why start work on a card game that clearly has no future?—and Nintendo likely told them “well, we’re working on a new game called ‘Pokémon Gold and Silver’, and these are just 14 of the new creatures which will be part of it… so I guess you can say that there are really 165 Pokémon at this point, just that only 151 will appear in the Red and Blue games being released”. They might have even been shown some Southern Islands product showing Showking, Marill, Togepi and Ladyba, which although wouldn’t release until 1999 as well, I’m sure they had plenty of behind-the-scenes material to show.

In any case, consider that 14 is the number we needed, and the number of G/S Pokémon revealed by this point in time is 14 as well. Coincidence??

What A MAJOR Deal!

PHEW!! What a HUUUUGE post today! Yep, well, these posts really do get my brain cells fired up, because of all the different ideas, elements, history and whatnot that are involved in trying to understand what I’m looking at. The fact that this prototype Blastoise card was revealed to the world is effectively the TCG equivalent of the Gigaleak that revealed all the Space World Prototypes to the world. OK, well, maybe not to THAT degree, but the concept is the same: it’s tapping into a hidden history of Pokémon which us mere mortals would’ve never otherwise known about. And now that we can finally see it, break it down and mine it for useful history, the fandom is scarcely the same afterwards. I mean, just look at what this one single card brought up? We touched on the history of Wizards of the Coast as well as the cloudy pre-G/S era of Pokémon, plus card design elements, lessons in efficient design, and even snuck in a few fan theories. Clearly this was a really big deal!

Anyways, hopefully more hidden bits of TCG history like this will be uncovered in the time to come… and when it does, you can be sure that I’ll be on top of it. … OK, well, three months after everyone else talks about it, of course. Good times? You betcha!

4 Comments

Great article !!! I have been thrilled to learn about this historical Pokemon card find. This seems to be the card that started the Pokemon craze in America. It should probably be in a museum…

Thanks for the comment, I’m glad you enjoyed reading it! Yeah, I TOTALLY feel you on this; this is such an amazing find, especially for such a simple and basic card. So much history is wrapped up in it, it’s a shame that there isn’t a museum for it to live in.

But hey, if that museum doesn’t exist, then it’s up to us fans to make it. In that case, I’m just glad we know of it to begin with.

Check it out…

Your article link is featured at http://www.TheMostImportantPokemonCard.com

Oh nice, thanks for the link back! It truly is one of the most important Pokémon TCG cards. Nice site documenting everything about it too!